Overseas IP lawyers with an eye on Australia might have noticed a flurry of reports on the High Court’s decision in Self Care v Allergan which was handed down last week.

The decision is notable for several reasons.

- It’s the first High Court judgment on trade marks to be issued by a majority female bench. And it affirms the original dissenting view of another female justice, Branson J.

- Related to point 1, perhaps, it’s a joy to read: immaculately reasoned, categorical and thorough. You couldn’t appeal it even if the Privy Council was still a thing.

- It’s momentous. It deposes a flawed principle that had dogged Australian jurisprudence for decades.

- It’s interesting for its determination on comparative marketing practices.

This article focuses on reason number three.

Deceptive similarity: a brief history

Deceptive similarity is a core concept of Australian trade mark law. It governs how most trade marks are compared for the purposes of registrability and enforcement. For an earlier mark to block registration of a later one, the marks must be deceptively similar. Similarly, for a registered mark to thwart use of an unregistered mark, the marks must be deceptively similar.

Over the last couple of decades, deceptive similarity began to lose its coherence, with courts and tribunals of all levels wrestling with the question of whether a mark’s reputation is relevant to the comparison exercise – and if so when and to what effect. In this article, we’ll refer to the idea that actual use and reputation bear on deceptive similarity as the Problematic Doctrine.

Following to the importation of the Problematic Doctrine from the UK into Australia, deceptive similarity became a soup: an illogical mess that undermined the carefully-erected dichotomy between the registered trade mark system and the common law tort of passing off.

In Self Care, the High Court strained the soup. It returned the concept of deceptive similarity to its principled origins, ousting the Problematic Doctrine and determining unanimously that reputation garnered through use is irrelevant to the comparison.

Deceptive similarity under the Trade Marks Act

Deceptive similarity is defined in section 10 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth). A later mark is deceptively similar to an earlier mark where it so nearly resembles it that there is a likelihood of confusion. The same test applies at the examination/opposition stage as at the infringement stage.

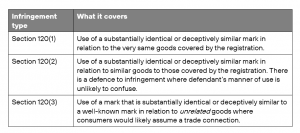

There are three kinds of trade mark trade mark infringement under the Act:

Where the action is run under section 120(2), it’s permissible to consider the actual use of the defendant in determining the application of a very specific defence. Where the action is run under section 120(3), it’s permissible to consider the well-known status of the prior mark and the likelihood of erroneous assumption as to trade origin. Section 120(3) is rarely invoked given the requirements that the prior mark be well-known but the goods unrelated.

There is no part of the Act that links reputation or use to whether two marks are deceptively similar. Deceptive similarity has a singular meaning and involves an accepted analysis. Questions as to “manner of use” and “well-known marks” under sections 120(2) and (3) are separate questions.

The right way to assess deceptive similarity

When assessing deceptive similarity, we’re trying to determine the likelihood that a consumer on encountering a later mark would wonder whether it shares a trade source with an earlier mark. The deceptive similarity analysis is quirky because it occurs in a sort-of commercial twilight zone. We build a hypothetical scenario that admits some market-specific realities but excludes others.

Here’s what we do.

We take the notional consumer, being the ordinary purchaser of the relevant goods. We credit them with a recollection of the earlier mark that’s everyday: neither crystal clear nor vague. The consumer’s memory of the earlier mark is an overall impression that includes the appearance, sound and meaning of the prior mark. We ask whether – as a rule – the consumer possesses particular skills or experience that makes them particularly discerning, attentive or careful. We consider whether – as a genus – the relevant goods are expensive or unusual purchases: if so, closer attention will be applied. Where the market is cluttered with closely resembling brands, this is relevant too: it usually suggests that small differences between marks will suffice to avoid confusion.

Importantly, we don’t attribute to the ordinary consumer any knowledge of the actual use or reputation of either mark. We do not consider that the registered mark has a celebrated history spanning many decades or continents or that the later mark is used under a disclaimer. Actual similarities and differences in price points, customer characteristics or sales territories – all those factors that are central in a passing off action – are irrelevant to the concept of deceptive similarity.

And for good reason. As Mark Davison explains in an article from 2013 that has lost no currency,[1] the entire trade mark registration system was introduced to avoid (or at least reduce) the tremendous costs of passing off litigation. Because of the breadth of the passing off enquiry and the relevance of all surrounding circumstances, evidence in passing off proceedings can quickly blow out: Davison cites one example involving a 26-day trial and 64 separate witnesses.

The attraction of the trade mark registration system in creating a distinct species of statutory property is that the scope of the rights granted by that system are defined by what’s on the Register. What creates an enforceable right is the act of registration, not what the registered owner did beforehand or since in commerce. And so it makes sense to compare marks by reference to what is on the Register, augmented by industry-specific but not party-specific commercial realities.

For almost a century since the establishment of our national trade mark registration system in 1905, parties to trade mark disputes in Australia reaped the full benefit of the registration system as described by Davison. Proceedings for infringement could be brought and won based on the likelihood of confusion arising from the defendant’s conduct assessed in the hypothetical context by reference to what appeared on the Register, supplemented by evidence of market realities as appropriate.

The Problematic Doctrine emerges

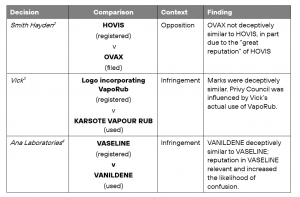

Post Second World War, three UK cases set the stage for the importation of the Problematic Doctrine into Australia. The cases established that a mark’s “great reputation” can be taken into account when assessing deceptive similarity.

To foreshadow something that would later become an unnecessary distraction under Australian law, it’s worth noting that from the get-go, reputation was conceived of a double-edged sword. It could work for or against its holder. In Smith Hayden, reputation reduced the prospects of confusion, perhaps because it perfected the consumer’s otherwise imperfect recollection. In Vick and Ana Laboratories, it increased the prospects of confusion, perhaps because consumers were more likely to assume that the junior mark was a variant of the senior mark and shared a trade source.

The troublesome doctrine is imported into Australian law

It took a few decades, but Australian hearing officers and judges began to follow the UK’s lead, importing reputation of well-known marks into the deceptive similarity assessment.

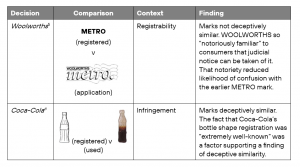

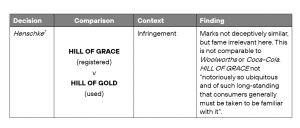

In 2000, the Full Federal Court expressed some ambivalence towards the Problematic Doctrine. It admitted to having difficulty accepting the relevance of fame. However, as the registered mark in that case wasn’t considered sufficiently well-known, the point was obiter and the Court didn’t need to rule on the Doctrine’s future in Australian trade mark law.

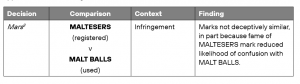

The Full Court’s next decision, Mars, swung the other way. The Problematic Doctrine was applied in full force but against the interests of the owner of the famous MALTESERS mark.

In 2018, the Full Court attempted to ratchet back the Problematic Doctrine, but unsatisfactorily. It reinterpreted Woolworths to mean that if a mark is so well-known that its reputation is relevant, this only ever works against the holder of the famous mark when the marks are compared (à la Mars). The idea is that fame crystallises a consumer’s imperfect recollection, so can only ever diminish the scope of registered rights. This finding is troubling: even if we accept the relevance of reputation for famous marks, there’s no reason it should operate asymmetrically.

The Meat Group decision could lead to the rather perverse situation where a defendant adduces evidence of the notoriety of the plaintiff’s mark in a bid to avoiding infringement liability, while the plaintiff downplays its own brand’s success [10]. How that would square with the evidence strategy in a tandem passing off action is anyone’s guess.

The High Court’s decision in Self Care

The relevant question in Self Care was whether Self Care’s PROTOX trade mark was deceptively similar to Allergan’s well-known BOTOX trade mark.

The trial judge said no: BOTOX was so well-known that confusion with PROTOX was unlikely. The Full Federal Court said yes: BOTOX so well-known that confusion as to product variant was likely. Both the first and second instance decisions considered the significant reputation of BOTOX in assessing deceptive similarity with PROTOX, but with opposing results.

On appeal, both parties abandoned the argument that reputation has a bearing on deceptive similarity. Presciently, as it happens, each party was prepared to argue its position in the old school (pre-Woolworths) fashion, based on a straightforward comparison of the marks in their notional contexts. Sensing its opportunity to rule on the Problematic Doctrine once and for all, the High Court appointed amicus curae to act as contradictors so the matter could be fully ventilated and determined.

The High Court dispatched the Problematic Doctrine in clear terms, holding (at 17) that reputation:

“should not be taken into account when assessing deceptive similarity under s 120(1). That conclusion is compelled by the structure and purpose of, and the fundamental principles underpinning, the TM Act”.

Aside from the text and structure of the Act, another justification for ousting the Problematic Doctrine was that it created tremendous uncertainty. As we know, cases have gone both ways on the issue of whether notoriety sharpens recollections for or against the holder of the reputation. Davison writes [11]:

“There is no indication in any of these cases of when the existence of a reputation will enhance a registered trade mark owner’s position and when it will diminish that position. So how does a registered owner know when it is in its interests to point out that its trade mark is well known and in its interest to argue that it is not so well known? The answer appears to be that it cannot know and, if that is the case, there is something seriously wrong with the state of the law.”

A related point is that the public needs to be able to rely on the Trade Marks Register as a true reflection of the scope of rights contained therein. If, as the Court observed, “[n]either the reputation of the mark nor the trade mark owner’s reputation is a particular on the Register”, then how is a trader supposed to size up the scope of registered rights, and thereby avoid infringement?

The Court also pointed out that the Act explicitly accommodates reputation in four discrete scenarios: registration of defensive trade marks, a ground of opposition to registration based on reputation in a prior mark, infringement of well-known marks (discussed above), and a ground of cancellation popularly known as “genericide”. Outside these limited scenarios, a trade mark owner’s monopoly is delimited by what’s on the Register.

Having ousted the Problematic Doctrine, BOTOX and PROTOX fell to be compared through the conventional analysis. Unsurprisingly, the marks were not found to be deceptively similar.

Conclusion

Those with a penchant for deep cleaning YouTube videos will understand the satisfaction brought by a good old-fashioned tidy-up. The High Court may have had a patchy history with trade marks [12], but this very significant judgment redeems.

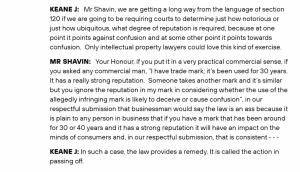

And for those concerned that ejecting the Problematic Doctrine means compromising the rights of successful brand owners, let us remember the words of Justice Keane in the Meat Group special leave application hearing [13]:

References

[1] Davison, “Reputation in Trade Mark Infringement: Why Some Courts Think it Matters and Why it Should Not” (2010) 38 Federal Law Review 231.

[2] Smith Hayden & Co Ltd’s Application (1946) 63 RPC 97.

[3] de Cordova v Vick Chemical Co (1951) 68 RPC 103.

[4] Ana Laboratories Ltd’s Application (1952) 69 RPC 146.

[5] Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd [1999] FCA 1020.

[6] Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 107.

[7] CA Henschke & Co v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd (2000) 52 IPR 42.

[8] Mars Australia Pty Ltd v Sweet Rewards Pty Ltd (2008) 81 IPR 354 (upheld on appeal).

[9] Australian Meat Group v JBS Australia Pty Ltd (2018) 363 ALR 113.

[10] Davison, op cit, 249.

[11] Ibid, 250.

[12] See New South Wales Dairy Corporation v Murray Goulburn Co-operative Co Ltd (1990) 171 CLR 363 and Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Modena Trading Pty Ltd (2014) 254 CLR 337 for one early and one late example of a contentious High Court trade mark decisions.

[13] JBS Australia Pty Limited v Australian Meat Group Pty Ltd [2019] HCATrans 105.